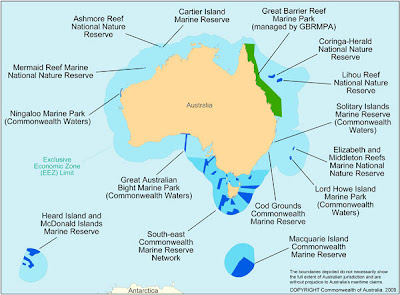

One of the bright spots in ocean conservation has been the worldwide adoption of marine reserve areas. From Hawaii to Australia to the Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean, marine reserves or parks that prohibit or strictly limit recreational and commercial activities are being recognized as a positive step in preserving delicate marine ecosystems and allowing biodiversity to flourish. A lot more reserves are needed but what we have is a start.

One of the bright spots in ocean conservation has been the worldwide adoption of marine reserve areas. From Hawaii to Australia to the Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean, marine reserves or parks that prohibit or strictly limit recreational and commercial activities are being recognized as a positive step in preserving delicate marine ecosystems and allowing biodiversity to flourish. A lot more reserves are needed but what we have is a start.But what defines a marine reserve? What is the method or methods by which the boundaries are determined? Well, this is where scientific research - past and ongoing studies - plays a crucial role. It requires research that examines a whole range of factors - biodiversity, population studies of specific species, water quality and movement patterns, topographical seabed mapping, and more. No one study can do it all, so research accumulates and from this wealth of knowledge, recommendations are made to determine the location and size of the protected area.

But not everyone agrees on the science. Lobbying forces that represent recreational or commercial fishing, and other business interests such as mining and mineral exploration, often question the validity and accuracy of the science. And so the battle rages for the attention and vote of the politicians and decision makers in charge.

Recently, Australia's Department of Environment, Climate Change, and Water commissioned an independent review of the scientific research used to determine its marine reserves, and the results heavily favored the available scientific research. Newly designated areas in New South Wales (NSW) had been heavily criticized, but it would appear by the review that the research that, both, had been done and was planned for the future was sufficient to support the marine reserves.

''The independent review panel found evidence of much ongoing or completed research and monitoring that has taken advantage of established marine parks within NSW,'' the authors of the review wrote, as reported by the Sydney Morning Herald.

''The independent review panel found evidence of much ongoing or completed research and monitoring that has taken advantage of established marine parks within NSW,'' the authors of the review wrote, as reported by the Sydney Morning Herald. ''These are resulting in presentations at conferences and scientific papers published in the international literature, and the reputation of the work being done is, on the whole, excellent.''

The Sydney Morning Herald also quoted Dr. Klaus Koop, the department's conservation and science director, who felt that marine parks not being supported by science was an idea that has been debunked. However, he did make one interesting observation.

''One of the things that we haven't done well enough, perhaps, is communicating exactly what we've done and … what we've found,'' Dr Koop said.

I am a proponent of good media communications for scientific research and that often means a lot more than just published articles in academic journals. Researchers need the assistance of those with media expertise, like myself, in communicating their work to a broader audience - one that includes policy makers, commercial interests, and the general public. The more the information is disseminated in easy-to-understand results and implications, the more challenging it becomes for opposing forces to dismiss or question its legitimacy.

Read the Sydney Morning Herald article.

No comments:

Post a Comment